(Originally published March 2016.)

Few things in life are as pleasant as awakening to the smell of freshly brewed coffee and frying bacon (for my vegan friends, you can ignore the last part of that sentence, but it does not change the fact…sorry.) Smells are time machines, for they can transport us back to long-ago places. To this day, I can’t smell Old Spice without feeling the strength of my father’s hug, and when a pot roast is cooking in the oven, I am back in the loving arms of my dear mother. Ah, “thank you” olfactory nerves…you are the best.

This story begins before dawn on a Texas summer day with the smell of bacon and coffee. The year was 1969, and I was enjoying my 13th year of life. Obviously, drinking steaming hot “Joe” was not a part of my daily routine; I would not adopt that habit for another two decades, and then only to stave off fatigue over the long, dark Pacific as a new Boeing 747 Flight Engineer. Saying that international pilots cannot fly without that heavenly bean would be a gross understatement indeed. But the bacon? That was another matter altogether. I think it’s fair to say that your average teenage male can consume his body weight in fried pork without too much effort, and I don’t doubt that on this particular morning, that theory was alive and well.

The destination for this day, and the reasons behind an excited teenager bounding out of bed at 0400, were part and parcel of an adventure that few (if any) teens can say they’ve been a part of. My dear Dad and I quickly devoured the forlorn pig (plus an egg or two), washed it down with several cups of “mud” (me having milk), and mechanically (and stealthily, I might add) began the process of gearing up for our hour-long drive westward. We were bound for a small, “one-horse town” on the ragged, scrub-brushed plains of North Texas, and after loading into the Chrysler Town & Country wagon, my dad would pour another cup of coffee from his green thermos, light up a Salem, and find some George Jones on the AM radio. Backing out of our slanted driveway on Westfield Drive in south Fort Worth, we turned west toward the entrance to the Loop 820 freeway, and off we would go. The eastern sky would be sporting a faint glow, the cicadas would be singing their nocturnal summer tune, and life could not be better.

(The “mini-van” of the 60s and 70s…the family station wagon.)

Mineral Wells, Texas, lies just east of the Brazos River, squarely astride the demarcation line between Palo Pinto and Parker counties. Its fame lies not only in its mineral springs, but the fact that in the year 1919, it was the spring training location for the Chicago White Sox (the year of their infamous “Black Sox” scandal). One other fact about this hardscrabble little village: in the year 1925, an outfit by the name of the United States Army opened its gate to Camp Wolters just a few miles down the road, and it would soon become one of the largest infantry training facilities during the Second World War with two famous people (for far different reasons) receiving their training at Wolters. Two Army privates…one named Audie Murphy and the other Eddie Slovik…one lauded with praise, the other not. Shortly after the war, the Air Force held the keys to the facility, but it was not truly back on the map until 1956, the year two remarkable events occurred. In that pivotal year, yours truly was born and spanked into life in an Army hospital in Schwabisch Gmund, West Germany, and the United States Army’s fledgling rotary-winged world opened its Primary Helicopter School on the sun-bleached plains just outside of town.

At this time in my young life, my father had recently ended his active-duty career, having “separated” from the Army, and our family had moved from Germany to Texas (our second tour in Deutschland, counting, of course, my “birth tour”). A few years earlier, he had spent his time in the skies over war-torn Vietnam, and after surviving that, had taken a “cushy” overseas assignment in the cockpit of the CH-34 Choctaw with the 7th Army just outside of Munich. Toward the end of his Germany rotation, he received orders to train in the CH-47 Chinook (his dream machine), with the ugly caveat being that his next assignment would be in that lovely machine, but back in the bloody skies of Vietnam. By this time in his Army career, he had served more than 20 years and decided to retire, letting the young bucks win the war (it was, after all, his second war…his first as a medic in Korea).

(My Dad’s ride in Germany, the CH-34 Choctaw.)

The question then became…what to do next? As any pilot knows, if you can secure an easy gig that pays well and remain in the cockpit, then take it! He found one, and it did, so he took it. As the 1960s waned, the demand for young men to fly the Army’s newest marvel of aerial warfare (the helicopter) was skyrocketing, but there was a large problem. The big hurdle was not finding the volunteers to pilot these things, but finding those who had earned the coveted Army wings and were ready to teach their precarious trade to said volunteers. The Army supplied numerous qualified active-duty pilots (most with time logged in Vietnam) to serve as instructor pilots, but that was still not enough to meet the ever-increasing demand for cockpit crew members. An enterprising outfit named Southern Airways stepped in and offered a solution. They would not only provide the lion’s share of the maintenance on the hundreds of helicopters at the blossoming facility at Ft. Wolters, and be responsible for many of the support duties on base, but they would hire hundreds of retired Army aviators, train them to be Instructor Pilots, and blend them into the Army Aviation Primary Helicopter curriculum where needed. It was truly a win/win/win for everyone (Southern Airways/the Army/AND the retired pilots). With that “marriage of convenience,” history was made.

Where and how my father found out about this gravy train is beyond me, but I would guess it was from within his network of Army pilot buddies. He began his second career in aviation in the late 1960s, and within a short period, discovered that he took to it like a duck to water — and so did his youngest son (me). From his comments to my dear Mother, I surmised the following; he loved the fact that he no longer had to wear a myriad of uniforms (his “work clothes” consisted of a zipper-infested flight suit, his old Army combat boots, and a baseball cap), he had very little paperwork involved other than the usual student forms, and he did not have to deal with 99% of the unpleasant things that came with many of his active duty flying stints. He was in heaven…albeit a strangely scheduled one. It seems that the Southern Airways Instructor Pilots (or I.P.s as they were known) worked an “early week,” then transitioned to a “late week,” on and off ad nauseam. The students would also be subject to this rotational ping-pong; they would fly in the mornings, complete schoolwork in the afternoons, and then rotate to the opposite schedule the following week. Strange to be sure, but so are many of the ways of the Army…hence our pre-dawn launch.

Roughly 30 minutes after leaving my slumbering siblings, we would pull off the massive I-20 superhighway onto the old “Ft. Worth Highway” (legally known as Texas State Highway 180). At this point, we would be just a few miles east of Weatherford, roughly 20 minutes from our destination, and the flavor of our drive would begin to change. My dad would start to lose his typical air of nonchalance while we discussed earth-shattering topics such as the upcoming season of the Dallas Cowboys, my last performance on the baseball diamond, or the football turf (he was the coach of my baseball team). His mind began its time-honored process of switching between the happy-go-lucky groundling to a serious, professional aviator (I notice I do it myself as I pull into the airline employee parking lot). I would react in the opposite realm, typically becoming more excited, knowing what lay in store for me that day, but I would sit quietly and let him sink into his thoughts. After all, every pilot has a “game face,” and he needed to slip into his.

(Map of north Texas showing our routing for the day.)

Before long, we would make the right turn onto Washington Avenue, pass under that iconic “Main Gate” sign, and I would be spellbound under those magic words: “Primary Helicopter Center” with the two beautiful rotary-wing machines, each standing guard on its respective side. Adorning the apex of the big sign sat a replica of the wings that I grew up seeing proudly displayed on my own father’s chest…those beautiful silver wings of an Army Aviator. That shiny symbol always represents to me such enviable qualities as: courage, honor, integrity, intelligence, and that AMAZING ability to hover! Passing underneath this metal and mortar “gate,” we would enter Ft. Wolters, but we would also be crossing a Rubicon of sorts…we had now crossed from the world of those who know nothing about helicopters to those who knew everything about them. I was in heaven, and I knew it. To me, it was akin to walking into a major league ballpark before a game; these folks were “different” than the rest of us…not a point of judgment, just a simple fact.

(The main gate circa 1969, with the OH-23D Hiller “standing guard” on the left and the TH-55A to the right.)

(The main gate as it looks today.)

By now, the sun would be low in the morning sky, portending another scorching, sweat-soaked Texas summer day, and as we drove toward one of the big heliports, my dad would be lost in his thoughts. As a former Flight Instructor, I can only surmise that they were of that day’s lesson plan with his three students. The civilian (Southern Airways) I.P.s would take the WOCs (Warrant Officer Candidates…they also had Commissioned Officers coming through, but I don’t recall if he had any of those type students), and take them from Day 1 (the orientation “nickel ride” as it were) through solo and on to some magic “stage check”, where they would disappear off to an actual Army I.P. for the rest of their Primary training. After graduation, they would disappear roughly 800 miles southeast to the red clay world of Enterprise, Alabama, and “Mother Rucker” (Ft. Rucker) for the remainder of their journey into the world of Army Aviation. From there, the vast majority of his students had but one destination…Vietnam. I am convinced that his time spent with these amazing young warriors was not only some of the most challenging flying he ever did, but also some of the most rewarding.

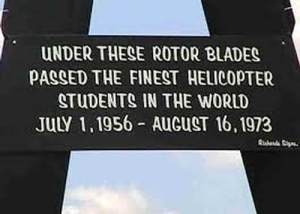

(These words under the crossed rotor blades always fill me with pride. They were indeed the finest, and he was one of them.)

The Briefing.

Pulling into the parking lot adjacent to the old, sun-washed building where this would all begin was tantamount to entering a quasi-world of the military (mixed with us civilian and ex-active duty types). Lots of loud olive-drab vehicles, groups of men all moving purposefully, the iconic checkered control tower looming over us, and, of course, the requisite huge ramp area where hundreds of little orange/white flying machines sat inertly, squatting in anticipation of flight. The crunch of the gravel under my tennis shoes was drowned out by the dozens of “size 10 combat boots” that my dad and the other I.P.s wore. They would greet each other with the time-honored banter of all aviators, and although most of the conversation centered around how each of them was in fact THE best damned pilot the Army ever constructed…at times the conversation would become hushed, and snippets of “by the way, I flew with your boy Jones last week, and….” At this turn, their faces would adopt a deadly serious expression, and I knew that I was seeing them deep within their element…and they were indeed the best at their trade.

(The massive ramp area of one of the main heliports.)

My father would hustle me into the big room, get me seated at his briefing table, fire up a smoke while pouring another steaming cup of coffee, and start paging through the folder of each of the three WOCs he would be flying with this fine day. Many times, I would be in their world at a “post solo” stage for these fledgling pilots, so their first huge hurdle had been successfully jumped. This meant that a tiny part of the mountain of pressure that they were living with had been relieved, and this translated into relaxation and fun for both the student and the I.P. Presently, the loud hissing of the air brakes from an Army bus would announce the arrival of said students, and the bright morning sun would invade the cool room as the door flew open, and in poured a couple of dozen boisterous, smiling, young men (many of them were far closer to my age than to his). I am not sure what they thought of me being there, and since I never saw any other dependents hanging out with their old man, maybe they thought I was some “junior, junior ROTC” type kid. I’m not sure, but they were always friendly and essentially just accepted me being there.

(A typical briefing room.)

This is where the proverbial rubber would meet the road for them (and me, in some ways). For now, the imparting of knowledge and quizzing would begin. My father had an easy way about him, with a smile that could disarm almost anyone, and this lent itself to an air of ease in learning. (Side note: I strove hard to emulate him when I became an I.P., and fortunately, I had very few instructors over the years who had the opposite teaching style, which was beneficial. When the berating would begin, the learning would end.) Growing up in this world, I had added a strange mix of vocabulary that did not exist in the normal lexicon of most teenage males. At this time in history, most American boys spoke in the language of such things as the wishbone formation, a double play ball, a Ruger .22 rifle, a Honda mini-bike, and the Cowboys versus the Packers. But thanks to my dear old Dad, you could add to my conversational English terms like translational lift, retreating blade stall, vortex ring state, pedal turns, auto-rotations, and about a million other little snippets from the world of Army Aviation. I must admit…I was a rather unusual 13-year-old kid.

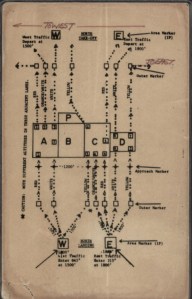

With the formal briefing now underway, I adopted a fly-on-the-wall posture. These conversations were chock-full of amazingly cool things, such as traffic patterns, visual approaches, landings, auto-rotations, and mastering that all-important art of hovering. I noticed that my father always had a big pad of blank paper on the briefing table. In later years, when all his students were young Vietnamese pilots (Google Richard Nixon and “Vietnamization”), he would end each instructional dissertation with “Do you understand?” This was (almost always) met with vigorous nodding of three heads, and a resounding “Yes!” He would then push the blank pad toward them with the comment…” OK, you draw for me what I just taught you.” This was (many times) countered with a blank look and a resounding, “I don’t understand!” …lol. I cannot imagine a more challenging task than teaching something as complex as rotary-winged flight to someone from a (mostly agrarian) third-world country. God bless the I.P.s and the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) pilots that teamed up to get the job done.

The Stage Field.

One of the ingenious ideas that the Ft. Wolters brain trust developed was the concept of dozens of relatively small training heliports scattered throughout the local area. These small training facilities became known as Stage Fields, enabling the huge facility to train literally hundreds of pilots simultaneously. Originally, they were given cool “cowboy” names, such as Pinto, Mustang, Bronco, and Ramrod. Later in the decade, as the war in Vietnam ramped up to its horrific climax (requiring thousands of additional chopper pilots), more Stage Fields were built and given monikers of actual in-theatre airfields. These were christened with names such as Hue, Chu Lai, Da Nang, An Khe, Bien Hoa, Soc Trang, and several others. Here’s an interesting tidbit concerning these little airfields: they were positioned in the same relative position as their real-world counterparts, thus allowing the newbie pilots to have a modicum of familiarity with the names and locations before they shipped overseas. Cool idea…right?

(Map of the Stage Fields.)

With the lesson plans and briefings complete, my dad and his three students departed for the massive ramp to begin their pre-flight duties on the venerable little Hughes TH-55 (the I.P.s dubbed it “the Mattel Messerschmitt”). With the morning heat and humidity building by now, yours truly would be bouncing across the plateaus of North Texas in a (very) used Ford pickup truck. For each shift, one member of the instructor staff in each flight would be tasked with driving to the assigned Stage Field, operating the “Unicom type” radio, and generally managing the compact little airfield. It was typically considered a cushy duty, for rather than spending hours in a hot, sweaty, cramped little cockpit, he got to hang out, drink coffee, and provide the pilots with needed information, such as wind speed, temperature, and the altimeter setting.

(One of my father’s traffic pattern cheat sheets.)

(Stage Field Pinto.)

I would ride shotgun with this man out to the Stage Field. After thirty or so minutes of dusty gravel roads, several cattle gates, lots of hot Texas wind (and several good pilot stories), we would arrive at roughly the same time as the inbound swarm of small helicopters that was darkening the horizon. What was our exciting destination for this day? A magical place by the name of Stage Field Sundance. The protocol would be that one of the students would ride out to the training airfield with the instructor, while the other two would fly solo to that facility. They would then spend several hours completing the day’s syllabus, and my dad would rotate between students in their respective machines.

(Stage Field Sundance)

Once at the Stage Field, I adopted the guise of a de facto mascot for the Instructor Pilots. These men were all former active-duty pilots who had served in Vietnam, and most of them had been decorated for their bravery and valor. In my eyes, they all stood 7 feet tall, had the Wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, and they all generally made John Wayne seem like a 98-pound weakling. To a man, they possessed a twinkle in their eye, a bounce to their step, and a spark in their soul that few people possess. Perhaps it was the job, perhaps it was the fact that they had survived a stint in Vietnam, or maybe they were just all happy fellows…I didn’t know, and I certainly didn’t care. In short, they were heroes of the finest order, and I felt honored to be allowed into their world.

What were my duties as said mascot, you might wonder? I was to keep the coffee pot percolating (this was back when coffee pots didn’t have fancy names/buttons/etc. ….you put in the water, the coffee, and basically boiled it to within an inch of its life), the snack machine had to be up and going, and generally just be ready to do whatever else they needed me to do, or “fetch” for them. Truth be told, I felt like my major job description was to stare at them, wide-eyed and speechless, and listen to their stories… of which there were plenty.

Within a few minutes of heading into the building at Sundance, it became evident that I was, once again, in the midst of a maelstrom of aviation activity. The radio frequency was alive with position reports, requests for landing instructions, and lots of other stuff that my neophyte ears could not discern. Nowadays, I routinely converse with air traffic controllers from nations all over the world. French, German, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, and yes, even those that are the most difficult to understand — the Atlanta ATC folks, lol. Back then, however, I was four plus decades removed from my current expertise, so I could barely make out the occasional word, but most of it sounded like a confused jumble of nonsense…but that didn’t matter. By now, I could hear the whine of dozens of little Lycoming engines and the steady beat of hundreds of rotor blades slapping the hot morning air. Looking out the yellow-aged window, I witnessed a stream of dozens of small orange and white helicopters forming a daisy chain and heading inbound to the Stage Field. Stepping out of the building and ignoring the glaring sun, my gaze was drawn skyward in an attempt to see them all…knowing that my Dad was occupying one of those small works of wonder.

The next several hours would be spent in a mix of excitement, exhilaration, and joy. I was in a world I barely understood, in the presence of men steeped in a society so closed that few (other than their own) had ever seen, and I was tolerated, accepted, and somehow even made to feel like I belonged in that strange place. I would sit transfixed by the constant noise of engines, the rhythmic beat of rotor blades, and the endless parade of little helicopters making their way around the traffic pattern. Auto rotations were as exciting for me to watch as they were for the I.P.s and students to perform (maybe not, but they were fun to watch). At times, one of the machines would make its way past me, close enough for me to feel the rotor wash of hot Texas wind, settle to a landing, and out would bound the instructor. Up the machine would rise into a wobbly hover, make its way back to the conga line of machines in the pattern, and the dance would begin again in earnest.

(The TH-55 “Mattel Messerschmitt”.)

(I still have my Dad’s TH-55 Manual…I would not trade it for a king’s ransom.)

The art of the hover.

A common trait of the Stage Fields was the presence of a huge concrete area used for parking helicopters. Still, more importantly, it was for learning that one thing a helicopter pilot can do that no other pilot can — hovering. It always seemed to follow the same pattern: a helicopter would amble over to the middle of the area (always steady as a rock… obviously, the I.P. would be at the controls), and it would settle gently onto the pavement. There would be a few minutes of the imparting of a brain trust (I.P. to student) in the sacred art of acting like a hummingbird. Upon completion of the unveiling of the most sacred of secrets to this unenlightened soul, the fun (or torture as it were) would begin!

The little machine would rise and begin a rock and roll dance, ALL OVER the football field-sized area! The nose would dip, then it would rear back up, drift left, then drift right, the little machine would shoot up, drop back down…and all the while the instructors that were observing (their students were in the traffic pattern doing solo work), and I would be laughing our proverbial heads off! As a 13-year-old (and one who had never tried this myself), I was afforded only a small amount of guffaw. Still, these men in their zippered “hero costumes” would laugh, point, slap each other on the back, and generally have way too much fun watching some poor I.P. out in the “rodeo arena” trying to teach what must have been surely the un-teachable.

(Stage Field Bien Hoa)

Eventually (after several moments of “rock steady” hovering… the instructor was obviously once again on the controls), the student would somehow solve the riddle of his inability to grasp this golden chalice, and the torture would be complete. To quote my dad, it was like trying to teach someone to rub their stomach while patting their head, while walking up and down a staircase, all the while chewing bubblegum…and at a critical moment, the I.P. would yell “SWITCH” and it would all be reversed with surgical precision and correctness! They all said the same thing…eventually, the “light bulb” would come on over the student’s head, it would “click” somewhere in the deep recesses of their grey matter, the little bird would hover over the same patch of ground (mostly) for the required amount of time, and the fun would be over…

…until the next little orange and white machine would taxi into the “rodeo arena”.

“NOW…out of chute number 7….being ridden by WOC Jones…..WIDOW MAKER!”

It was a type of fun that few (if any) other young teenage boys can say they were ever a part of. Apparently, these “square-jawed,” “steely-eyed” Instructor Aviator types had all forgotten about their time in the proverbial barrel, and how inept they looked trying to hover when they were a bottom-feeding newbie. I’m certain they were no more adept at this dance than “WOC Jones” and his embarrassing maneuvering. My Dad used to say that if you could detect movement in the flight controls while hovering, then you were overcontrolling the machine — it was more about “thinking” yourself into the maneuver.

As an avid flight simulation enthusiast, I have often wondered (and have put these thoughts into writing a few times) what my father would think about the current state of flight simulations. Hovering the UH-1H “Huey” in DCS (Digital Combat Simulations) can be challenging, but would he believe it is even close to the real deal? My guess is that he would love it, spend my inheritance on a new PC rig, and I would never hear the end of it from my dear Mother.

(Yours truly flying the UH-1H “Huey” in the flight simulation DCS World)

All too soon, the day would begin to wind down, even though it was only lunchtime to my young body; I would have put in a full day. I would be riding high on adrenaline for hours, flush with thoughts of the heroes, and the sights, sounds, and yes, the smells of my time in their world. Funny, but it seemed that when those amazing men told their flying yarns, they often spoke of their awe of the OTHER pilots, their crewmembers (Crew Chiefs and door gunners), and they did it with a love and admiration that reminds me very much of how I speak of my beloved family. These men obviously loved their craft, their machines, but mostly their fellow airman. When my father returned from his tour in Vietnam, and I inquired about his medals, the question was always met with a “no big deal…they asked for volunteers, I simply raised my hand” type response. I would find out later that he had stepped up to fly into danger to pick up downed friends. I know ALL of them would have done it for him without skipping a beat. Such are the men (and women) of the Armed Forces.

One sad note.

Quite often, my Dad’s students would take a huge liking to him, just as he did to them, and many a time he would return home from Ft Wolters (after a class had graduated) with a symbol of that bond. It was usually in the form of a brand-new coffee mug with three names emblazoned on the side (and a requisite bottle of Jim Beam… lol). It was their way of saying “thank you” to a man they came to know, his knowledge they came to live by, and a person they learned to trust and admire.

Unfortunately, I’m sorry to say that on far too many occasions in those sunset days of his flying life, I would see him arrive back at our humble home with sad eyes and a heavy soul. He would sit at the kitchen table and speak in hushed tones to my mother, and they would stare at each other… knowing a thing that only they could know. Later, I would hear (from her) that he had been given the news that one of his students had perished in the crucible of combat in Vietnam. I truly know from within my heart that he would spend the remaining hours of that day searching HIS heart to once again see that young man’s face, to hear his excited “I have the controls” when my dad would give him the machine. I know that he would find that face, and a small piece of my dear father would perish along with that young man.

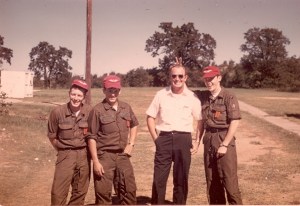

(My Dad as an I.P. with three of “his” guys…can you tell they liked him? Is it just me, or do they look too young to be doing what they were doing? I guess I have simply grown too long in the tooth.)

Side note on the above photo.

One August morning a few years ago, I was flying back from Anchorage with an older captain (he was crewing the Boeing 747) in the jump seat, and he inquired about the weather in the Minneapolis area during the two weeks he had been flying his trip. I casually commented that it had been so hot/humid that one would have sworn you were in North Texas. He quipped something on the order of “I spent some time in North Texas in the early 70s when I was in the Army.” This (of course) piqued my interest, and when I asked “where?”, his answer…”Mineral Wells…well, Fort Wolters” floored me. I relayed the gist of the above story to him, and this naturally led to a conversation about his experience going through Primary helicopter training as a new Warrant Officer before he went to Ft Rucker to complete it, then off to Vietnam. I inquired if any of his early instructors were the civilian pilots for “Southern Airways”…he answered, “yep, all of them.” I turned around in my seat and quipped, “Did you fly with a pilot with the last name of Ball?”, he answered, “What did you say your last name is?” When I answered, his eyes got huge. He exclaimed…”YOUR DAD was my I.P.!!! I have some pictures at home on my computer! When I get home, I’ll try to find them and send you some!”

We…naturally…. spent the rest of the flight chatting in amazement (to the boredom of the First Officer, I might add…lol), and it was amazing. A second unbelievable part of this incredible story was that he and several of his classmates (also students of my dad) attended his funeral in February of ’93! He said he remembered seeing his son [me] in my airline uniform…and when asked why he did not introduce himself, he offered that “it was a traumatic time for your family and we didn’t want to bother you”…I, of course, said it would have been one of the bright spots of a very difficult day. When I got home from the trip a few days later, the above photo was among others waiting in my email “IN” box.

Many times, flying for a vocation takes as much as it gives (lost time with family, missed birthdays, dance recitals, the list is almost endless). There are times in every aviator’s life when it takes a toll that is nearly too much. But sometimes, every so often, as in my days spent as “the Sundance Kid”, it gives more than you can ever imagine. My days spent with my dad (and his contemporaries) on those funny little “airports,” spread across the hot, humid scrub-brush plains of north Texas, will live with me till my end of days. I hope to someday sit with him again, in the clouds of salvation, and speak of those times. We will laugh and he will flash that “million dollar” smile, and I will be sure and remind him of his days spent teaching the “art of the hover” to all those young WOCs (and one rather weird 13-year-old little boy).

“Thank you, Pop…thank you.”

(You cannot hover the B757…but if you could…if you only could.)

‘till next time.

Went through officer basic in 1968, Red Hat. Ist Cav 1969, IP at Wolters January ’70-June ’71. Well done.

LikeLike

Bob,

Thanks for the kind words (and your service). Having never served, but growing up in an “Army family”, and being the proud father of an active duty Major, I feel a special bond with the Army in general, and “Army Aviation” in particular. The time I spent with my dear father at Ft. Wolters, were some of the most enjoyable and interesting days in my young life…and I’ll cherish them forever. The blessing of actually witnessing the man I deemed a hero DOING his heroic deeds, was nothing less than a gift that few can say they too were blessed to receive.

Thanks for stopping by the blog, and thanks again for the kind words. “Gary Owen…”

LikeLike